|

|

|

Islam

and History of Israel

|

|||||

|

Original

Title : A

new Paradigm for the Rise of Islam and its Consequences for a New Paradigm

of the History of Israel

|

|

||||

|

Originally

appeared in The Journal of Higher Criticism Nr. 7/1, Spring 2000,

pp. 23-53

|

| I.

- The new paradigm for the Rise of Islam |

|

|

Prophetic return

to the "High-Place-Religion," postponement and concealment of

this return by post-prophetic Islam1) But since the middle

of the 19th century, Arabists and Islamists have already discussed many

facts of the pre- and proto-history of Islam by means of contradictions

with the traditional view of the genesis of Islam. Pre-Islamic Arabic

poetry (in the main authentically transmitted) contains copious Koranic

ideas and phrases long before the revelation of the Koran. And there is

the general problem of the linguistic situation of pre- und proto-Islamic

Central Arabia discussed as early as the 19th century. Carlo de Landberg

(1848-1924) and Karl Vollers (1857-1909) contested with good reason the

dogmatic tenet of the Islamic tradition that the sophisticated Arabic

used in the classical Arabic poetry and known from the canonical Koran

dominated the public life of Central Arabia already at the time of the

prophet Muhammad, and they claimed to acknowledge the overwhelming dominance

of popular tongues and a vernacular language (koine) in pre- and proto-Islamic

Central Arabia. And on the basis of these data Karl Vollers tried to prove

the existence of a vernacular "Ur-Koran," whlich had in postprophetic

times been recast into a standard-language-shaped piece of literature. These paradigm-destroying results are on the one hand those of the Leben-Jesu-Forschung of Protestant theology, essentially those of Albert Schweitzer and his Swiss pupil Martin Werner. These results were made known to the English audience by S.G.F. Brandon's translation of Martin Werner's Die Entstehung des Christlichen Dogmas (Bern 1951 = The Formation of Christian Dogma, London, 1957). Of equally great importance is the research into the pre-state societies built on family, clan, and tribe relations and regulated by blood feud and the right of hospitality (asylum). These findings, essential for the insight into the pre- and proto-Islamic state of affairs, emerged from two different fields of research, namely Old Testament studies (W.F. Albright, Otto Eissfeldt and others) and recent social-anthropology and ethnology (Arnold Cenlen, Claude Levi-Strauss, A.E. Jensen and others). For the overthrow

of the orthodox Islamic paradigm for the rise of Islam, the linguistic

and literary-historical research in the Koran surely plays a central role.

But all the attempts begun since the end of the 19th century (D.H. Müller,

Rudolf Geyer, Karl Vollers) to elucidate the history of the editing of

the Koran via reconstruction of the original strophic and koine-Arabic

text, could finally succeed only after the addition of the critical Christian

theological arguments as welcome reinforcement, so that arguments out

of two totally different and independent departments of knowledge could

verify one another. If, for instance, the formal reconstruction of a rhyme,

which had been removed by the Koran editors, simultaneously revealed a

new meaning of this text which agreed much better with the new critical

insights into Koranic theology, then this reconstruction of the text of

the "Ur-Koran" had for the first time really obtained cogent

evidence because of its being proved out of two different and independent

areas of knowledge. By the same token, if a questionable theological Koranic

statement could be corrected on account of new dogma-critical findings,

then this dogmatical correction could be acknowledged as clearly proved,

if it at the same time revealed a better fitting form of the text, ideally

a rhyme which had been formerly suppressed. This double line

of argumentation to verify the existence of strophic hymns and a vernacular

in the Koran is finally further strengthened by numerous variant readings

of the Korantext, handed down to us by Moslem Koran scholarship, which

have always been regarded as only formal (i.e., orthographic, etc.) and

meaningless but which now turn out to be the specifically dogmatical relics

of the suppressed "Ur-Koran." These variants indeed constitute

a third category of evidence for the reconstruction of the "Ur-Koran."

However, new or even

spectacular findings in the linguistic and literary-historic field did

not result from the definite verification of the "Ur-Koran"

thesis of the turn of the century. The only novelty is that all that we

did already know about early Islamic and medieval Arabic strophic poetry

and vernaculars is now clearly to be found in the Koran, and this doubtless

as a Christian-Arabic literary product of pre-Islamic times, at least

of the sixth century C.E. This result is putting all previous reflections on the dependence and originality of the prophet Muhammad, as well as all previous chronological arrangements of the Koranic suras on a very new and different basis. But much more important than this now indispensable reshuffling of the chronology of the genesis of the Korantext is the readjustment of the new theological aspects which have appeared after the break-up of the traditional paradigm of the rise of Islam. To give only one example, I should indicate the now evident fact that the prophet Muhammad did understand himself to be an archangel, an "angel of the High Council (of God)" (LXX Isa 9:5f.: angelos tes megalas boulas), and that he implicitly wanted to be understood by his adherents as such an archangel. This reticence of the prophet in his self-designation as archangel has its own dogmatical logic and corresponds therefore exactly to the 'Messias Secret' of Jesus,2), that is that Jesus did understand himself as archangel-Messiah and wanted to be understood as such by his disciples and adherents but that he refused and interdicted (Matt 16:12ff.; Mark 8:27ff.; Luke 9:18ff.) to be in his lifetime expressis verbis declared and publicly preached as this Messiah. This obvious archangel-quality of the prophet Muhammad in his estimation of himself has the logical consequence that the prophet could on no account have been dependent upon the archangel Gabriel as mediator of the revelation as commonly related by the post-prophetic Islamic tradition. Not only the ubiquitous legendary occurrence of the archangel Gabriel in the Islamic biographies of the prophet, but also the obviously accidental and additional occurrence of this archangel Gabriel in the Koran (2.97f.; 66.4), agrees with this logical conclusion. So the ursemitic and ur-Christian angel-prophetology of the prophet Muhammad is a strong argument for the judgment that these Gabriel-citations in the Koran should be ascribed to the hand of a postprophetic Koran-editor. But these dogmatical problems of the Koran are of secondary importance here. The main problem, which has arisen out of the break-up of the traditional paradigm of the genesis of Islam, is what cannot be harmonized or reciprocally interpreted by means of Jewish and Christian dogmatics, that is to say, those points in which the pre- and proto-Islam shows a clear and steady opposition to the Jewish and Christian religions. The traditional Islamic paradigm, which sees Islam as an evolution from pagan polytheistic heathendom to monotheism, has never been very plausible because it could not explain how a prophet Muhammad, who allegedly had received only at a very late time gradual and vague information about the awe-inspiring doctrines of the Jews and Christians, could suddenly turn and adopt an intransigent attitude towards these doctrines. The most important

discovery emerging from the difference between the reconstructed strophic

hymns of the Koran and the genuine Islamic texts in the Koran added later

to these Christian hymns, is that the movement of the prophet Muhammad

was not, as the traditional paradigm pretends, a movement from pagan heathendom

towards the allegedly only insufficiently known monotheistic religions,

but on the contrary a movement from these properly distinguished religions

back to the religious and moral principles of the Central Arabian heathendom,

and in particular back to the High-Place-religion, to the cult of the

gannat algibali kama hiya, as Waraqa b. Naufal said, shuddering,

in one of his poems. This return means a return to what is considered

in the Jewish tradition as well as in post-jesuanic Christianity as the

non plus ultra of wicked godlessness. Serjeant demonstrates

that the prophet constructed his religious community according to the

religious and social principles of the millenia-old system of asylum around

sacred enclaves which can fairly well be recognized as old-semitic (=

early Israelite) High Places. At the same time, Serjeant shows that these

ur-Islamic religious and social traditions were from the beginning of

the second half of the first century AH onward suppressed and abandoned.

These findings of Serjeant consequently do manifest what the successful

reconstruction of the Ur-Koran brought to light in another way. Also Tryggve

Kronholm concluded recently: "We are bound to research in another

direction than those of Jewish, Christian, Gnostic, Manichaean, Zoroastrian,

or whatever impulses, when looking for the milieu in which the natural

dependence of Muhammad is rooted, viz. that of the traditional culture

of pre-Islamic Arabia, as we know it from the literary remnants of the

Jahilya."3)

. The fact that early

Moslems showed great fear and disappointment about every theological dispute

with Jews or Christians was discussed within the research on Islam at

the turn of the century,

4)

but it did not find the attention it deserves. As a motive for certain

tendencies in the post-prophetic editing of the Koran it is now of great

importance because an essential intention of the early removers and concealers

of the prophetic return to Central Arabian heathendom was to change the

original radical-prophetic opposition against Judaism and Christianity

to a "moderate getting along one with the other." This appeasement

was obtained by the introduction of a new picture of the genesis of Islam

turning the true one upside down: that Islam had been a movement turning

away from Central Arabian heathendom to found a "state-supporting"

monotheism like that of the Jews and Christians. Therefore, the only considerable

result of research in the Koran and Islam which exceeds the themes sufficiently

discussed since the turn of the century is the rediscovery of the prophet's

return to the spirit of the High Places most hated by all Jews and Christians.

That means that the central issue is to answer the question how the prophet's

return has to be understood. For surely that explanation is no longer

worthy of belief, which the Christian Occidental self-righteousness of

the 19th century would have given: that the prophet entered by this return

the service of Satan. Even conservative occidental Islamists have long

been ready to acknowledge that the activities of the prophet Muhammad

are only comprehensible as the outcome of a completely sincere endeavour.

Therefore, it is, so to speak, the necessary vindication of the prophetic

honour which stimulates the research to understand the essence of High-Place-religion:

the prophet must have been striving after something positive! After what? |

|

| II. - The new appreciation of 'High Place"-Religion | |

|

The new appreciation

of "High-Place"-religion in the context of the archaic conception

of the world. It should be clear that we cannot present all the evidence in our limited

scope. The following ideas can only be put forward in the form of theses

with commentaries and some hints at previous research. Commentary:

The first impulse to this understanding was given by William F. Albright

in his paper "The High Place in Ancient Palestine" (Suppl. to

VT, Congres Strasbourg 1956, Leiden 1957, 242-258). Otto Eissfeldt had

a similarly objective attitude towards the cult of the High Places in

early Israel. 6)

The objections which

have been put forward against Albright's assertion by the clerical conservative

theology are untenable, as I demonstrated in several essays.

7) Commentary:

the most important arguments for this equation ("cult of High Places"

= Messiah-cult) follow under thesis 3. Here we may only briefly point

out that "anointing," underlying the notion of "Messiah,"

has much significance in the cult of the dead ancestors. This is also

to be seen in the sacrament of the (deathbed) "extreme unction"

still practised in the Catholic church. Thus we have quite

different, 12)

and mutually independent

reasons for stating that the Old- and New Testament Messiah is, in origin,

closer to the limping High-Place-priests of the Baal of Jezebel, the Tyrian

Princess and wife of the North Israelite king Ahab (875-852 BCE), than

to the "orthodox" Israelite adversaries of the Baalim of the

High Places. But it must be taken into consideration that this North Israelite

cult of Baal of Ahab's time must already have been considerably distorted

because of its integration into the state-cult, which means remoteness

from the parent blood-feud reality of the tribes. So we can start from

the assumption that the New Testament Messiah does not derive from the

Tyrian cult of Baal, but stems from a tradition which preserved the native

blood feud idea of "the shepherd, who giveth his live for the sheep,"

reasonably unhurt by progressive state-doctrinarian distortions. Thesis

4: |

|

| III. - On the Israelite prehistory of the High-Place-Islam | |

|

Julius Wellhausen

assessed the old Arabic blood-feudal society as "on a very primitive

level" and emphasized "that it was not particularly effective."22)

This questionable

verdict will be forgiven him in view of the standard of ethnological knowledge

in those days, and we will also note in his favour that in his time the

possibly irresistible consequences of the steadily growing efficiency

of industry-imperial culture had not yet been discernible. It is this

questionability of the occidental effectiveness which makes it advisable

to see the surely - in terms of growth of materialistic wealth - not very

effective blood feudal society of the High-Place-religion with new and

totally different eyes from Wellhausen and his contemporaries. Wellhausen's

time-bound partisanship for the high-cultural imperial state and against

the "Gemeinwesen ohne Obrigkeit" is, in the last analysis, the

reason he confirmed the wrong judgments of his time in the field of Arabistics

and Islamics and established them with his authority.23)

For it is indeed uncontested that there has been in Israel through all

these different periods, on whichever level of cult-development, a hierarchic-centralistic

state-supporting priesthood. It has now become much more important, that

since the time of the Patriarchs there runs parallel to the Israelite

priestly tradition, inspired by hierarchic-centralistic high culture and

leading finally to Jewish orthodoxy, an opposing decentralistic, anti-priestly

line of tradition, which could maintain surely, with at least the same

moral right, and has maintained, the claim to be, ever since Abraham,

the true Israel, and which extends into primitive Christianity and Ur-Islam.

(By contrast, Hellenistic Christianity and post-prophetic Islam are assimilations

- the first aggressive, the second defensive - to the continuing tradition

of the religiously supported state.) As the guiding research for the new

paradigm of the genesis of lslam had already been done around the turn

of the century, so also for the new paradigm of the biblical history since

the Patriarchs as the history of parallel running lines of traditions.

We will put the most important aspects of its results in a row, confining

the scope on account of our special reference to Islam in the time since

the installation of monarchy in Israel: Another theme likewise perplexing for Islam-scholarship because it does

not fit with the traditional paradigm, is that of the idols, especially

the idols Isaf and Na`ila at the pre-Islamic Kaaba. What Islamic tradition

tells concerning these idols can be divided into two parts: either this

information is reasonably concrete and credible, in which case it is obviously

referring to images of Christian Saints, or this information is fantastic

and incredible, and then refers to the allegedly Central Arabian heathen

idols. The conclusion suggests itself that all "idols" at the

Kaaba were but images of biblical Saints and that the fanciful invention

of heathen idols corresponds to the tradition perceptible everywhere in

Islam of disguising the real conditions of religious life in pre-Islamic

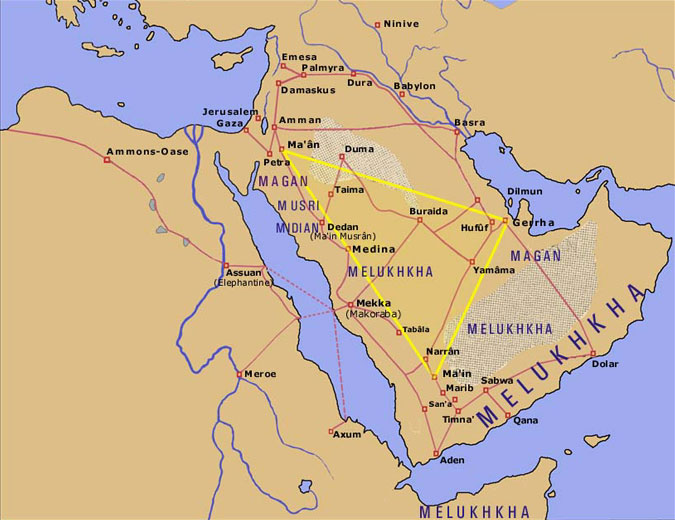

Central Arabia. Their argumentation rests fairly firmly on the basis that according to cuneiform information the north-western region of Arabia south-eastward of the Gulf of Aqaba was, until the 7th century BCE, named Musri (or Musur, Must, Misr) and that Israel had cultivated intense relations with this Musri, with its Simeonite / Ishmaelite population. Where still nowadays Egypt is in Arabic named Misr and in the Hebrew Bible Misrayim (= dual: two misr), it is all too easy to confound erroneously or intentionally Musri/North-West Arabia with Misr/ Misrayim/Egypt. Hugo Winckler in particular has pleaded with weighty arguments for the thesis that only with the conscious and/or unconscious indentification of Musri/North-West Arabia, occurring in old Hebraic texts, with Misryaim/Egypt did there develop in post-exilic times "the lay of Israel's stay in Egypt."35) In present Hebrew

Bible scholarship forces are stirring which plead for the same thesis

of a post-exilic origin of the exodus from Egypt narrative 36)

but without any reference

to the weighty argument of Hugo Winckler, the equation "Musri = North-West

Arabia." This argument seems to have been totally driven out of the

range of vision. I found the last emphasis laid on this equation in Trude

Weiss Rosmarin, who wrote in 1932: "Although the majority of research

workers hold Musri throughout to be Egypt, I want to refer with Winckler

and Hommel to an Arabic land Musri, which must have lain in the northern

part of the Arabian peninsula." 37)

This equation "Gurhum

= emigrants of Gerrha" has now again been represented in modified

form by Toufic Fahd. The essential improvement on Dozy is that Fahd for

the first time definitely localizes Gerrha, pointing out that it is not

to be identified, as hitherto by mistake, with the place al-Ga'ran near

al-Qat'if. Fahd takes as a basis of the name Gerrha the Arabic place-name

g·r·h

42)

But this speculation, already undertaken by Dozy, about the relation between

the people-name Guthum and the town-name Gerrha, can be given a better

foundation. I would like to assert that gurhum is the retrograde formation

of a singular from a word gerahim, which should be regarded as a Hebraic-Aramaic-Greek

influenced formation of a plural to designate the inhabitants of Gerrha,

i.e. for gerahi, "someone from Gerrha." T. Fahd does not go

as far as to claim this origin of the name Gurhum. He contents himself

with the statement that the people of Gerrha were "Araes arabisés,"

"emigrés Araméens". 43) |

|

|

|

©

2001 Dr. Günter Lüling Grafik: Kairodata Mediendesign

|

|

That Levites are found with the Minaeans can be explained by the degradation of the Levites by the cult-reform of the Judaean king Josiah (640-609 BCE), i.e., the centralization of the cult into the Temple of Jerusalem while banning all cult-places (from old High Places) in the countryside, of which the Levites had been the priesthood. Related to this disdain seems to be the fact that at the end of the Babylonian exile surprisingly few or almost no Levites returned to Judaea (cf. Ezra 8:15-19: no Levite is to be found among those willing to remigrate and only after a special mission could two Levite families be prompted to join). It is therefore not astonishing that we can find in the Talmud the hint that in the army of Nebuchadnezzar (605-562 BCE) 80,000 young Jews of priestly origin were serving, who were afterwards to settle in Central Arabia.48) Only the current false opinion that the people of Israel had throughout its history always been an unswerving uniform community without shocking rebellions and permanent desertion has condemned these and similar traditions to insignificance. And Jewish repression of this seamy side of Jewish history is most probably the main reason for the abiding uncertainty in the evaluation of the Minaean problem. In his book Kritische Beiträge zur Entstehungsgeschichte des Christentums (Berlin 1906), Bernhard Kellermann has a chapter "Das Minäer-Problem." However, he does not mean by this the South-Arabian and Midianite-Dedanite Minaeans, but the Minim, the Israelite heretics populating all cardinal points but especially the East. For the church-historian Jerome writes: "Usque hodie per totas Orientis synagogas haeresis est, quae dicitur Minaearum."49) An imprecation in the 12th prayer of the Shemone Esre of the synagoge is dedicated to these Minim/Minaeans: "And may the Noserim and the Minim suddenly perish. Let them be blotted out of the book of the living, and not be written with the righteous" (cf. Ps. 69:28). Jewish scholars have understandably always been disposed to explain the Minim as Jewish Christians 50) On the Christian side this explanation has never been very impressive, 51) not only because in the Shemone Esre the Noserim (Jewish Christians) are separately mentioned next to the Minim. Even according to Rabbinic tradition, the Minim are people who originally and essentially belong to the Israelite custom and tradition, but who are looked upon by Jewish orthodoxy as excommunicated because of heresies. And these heresies are above all that the Minim disapprove of monotheism, believing in more than one creative power 52) (which can not be claimed as Jewish Christian belief but which matches the commonly polytheistic faith in preexilic Israel!) 53) and that they are rather worldly orientated, therefore also being classified as Epicureans (likewise not a Jewish Christian feature!). 54) They are numbered among merchants (of long-distance trade?). 55) Least fitting of all to the equation "Minim = Jewish Christians" is the fact that, again according to Rabbinic tradition, the Minim represent a problem which was already acute in pre-exilic times and which also in Alexander the Great's days harrassed Jewish orthodoxy. 56) But this epoch, from the beginning of the Babylonian exile to the rise of Christianity, is precisely the flourishing period of the Minaeans, of the incense trade Minaeans of Central Arabia (Ma'in and Ma'in Musran). So we are already, on the basis of these data, entitled to identify the Minim (Jewish heretics) with the Minaeans (the incense-merchants of South- and Central Arabia) and equate these with the Guthum of the Arabic tradition. (The later heresy "Christianity" we can, without more ado, neglect as a special variant of the Minaean.) Now we will support our equation "Minim = Minaeans" with an inquiry into the circumstance that among the incense-Minaeans at Ma'in and Ma'in Musran, Levitism played a certain role: First of all, we

have to keep in mind that since at least the sixth century BCE the Minaeans

cut a great (if not the decisive) figure in the incense-trade all over

Central Arabia. But for this Minaean role the history of the incense-trade

in the preceding centuries is of importance. And behold, this incense-trade

had in this earlier period obviously lain in the hands of the Simeonites

/ Ishmaelites who had seceded from Israel around the turn to the last

pre-Christian millennium. For it is they who had become the heirs of the

Amalekites after defeating them - and as Hubert Grimme already detected

in 1904 from their name, 57)

these Amalekites were none other than the "incense-people,"

because the common word in cuneiform texts to designate the incense-land,

Melukhkha, is derived from the root from which also the word Amalek is

established. As Eduard Glaser could register, in South Arabia even today

incense is referred to as lamlokh

58)

(I add my thesis, that the classical Arabic

m·l·q is the correlation to this, compounded of ma

la'iq. This means that here a semasiological parallel to "Aithiop"

belonging to Arabic 'atyab,

"good, pleasant," is at issue.) If therefore the Simeonites / Ishmaelites became, after their victory over the Amalekites, "the incense-people," having taken over the job of the defeated, and if, which seems reasonable, the predominantly Levitie Israelite emigrants of the first wave (= first Guthum) after cult-centralization and the destruction of the first Temple leaned, as a help for their start in the new situation abroad, upon their former Israelite compatriots, the Simeonites / Ishmaelites, then this would have the consequence that these predominantly Levitical emigrants became, likewise, incense merchants 59)

And this corroborates our thesis, that Minim, Minaeans, and Gurhum are

essentially identical - the ones named according to their status as heretics,

the other according to their status as refugees (gerim) and the "town

of the refugees," Garrha. (The common equation "Minaeaus = Ma'inim"

is apparently a contamination, which cannot be discussed here).60)

The Minaeans as

"incense-people" were settling not only in Ma'in but nearly

everywhere, in any case besides Dedan also in Hadhramaut and Kataban.

It should be taken as certain that the Gerrhaeans/Gurhum could be, when

appealed to as heretics, called and were called Minim/Minaeans. This is

a matter of pure synonyms!) The "many relationships" were warranted by the above supposed

kinship of the Minaeans/Gurhum, who were, having followed the distribution

network, established throughout centuries by the Simeonites, sitting everywhere,

e.g., surely also in Punic Carthage. And the heretical Jewish colony of

Elephantine should also be better understood as a trade-colony on the

route Mecca-Carthage, since on the whole the more fitting picture of the

dispersion of the Jewish religion is that Jewish orthodoxy could everywhere

follow, and has followed, the traces of the incense-Minim. These circumstances not only explain the peculiar dichotomy of the population in Minaean South Arabia into chieftain of tribe and tribes-men, on the one hand, and Kabir ("elder of the trade-colony") 65) and his community, on the other (which correlates with the dichotomy "autochthonous South Arabians" and "immigrated Minaean charges"). These circumstances also throw light back onto the pre-state, even pre-Mosaic situation within the early Israelite federation of tribes, faced with which biblical scholarship has been somewhat at a loss since Martin Noth's amphictyony thesis was abandoned. This amphictyony-thesis had been a retrojection of the religious and cultic conditions of the monarchic-theocratic constitution of the Jewish religion into early Israel. But early Israel had been organized on blood-feudal, i.e., High Place lines; and where an incredibly stable continuity of blood-feudal High Place practices to maintain confederacies, as depicted by Serjeant and Puin, obviously reaches from early Minaean times into the Yemen of our day, we are allowed to reckon with a similar continuity from the Simeonites' victory over the Amalekites (ca. 1000 BCE) until the Minim / Minaeans. In the heralds of the blood feudal chieftain equipped with colours and drum, as depicted by Serjeant, we can rediscover the Levites, 66) i.e., the servants of the blood feudal system at the High Places of the early Israelite tribal confederacy. Because these early Israelite Levites were consecrated to the High Place sanctuary, this consecration meant, according to blood feudal belief, adoption by the hero of the High Place. And this explains why the early Israelite Levites, after they had been convinced by "Moses from Musri / Midian" to introduce at all High Places Yahve as the only one intertribal God, became a thirteenth tribe of Israel: as long as they had been consecrated to the hero of the sanctuary, they had become adoptives of these different eponym tribes. But since they were consecrated at all sanctuaries in all tribes likewise to the newly introduced one intertribal God Yahve, they then and they alone and nobody else of the regular tribesmen-became adoptives of Yahve and thereby a special tribe of Yahve-servants. 67) When the blood feudal faith at the High Places had been driven out and

conclusively abrogated in Israel by the cult-centralization, these specialists

of blood feudal constructions of sacral peace and inter-tribal federations,

the Levites, apparently did not eat humble pie and join the centralized

cult at the Jerusalem Temple as grudgingly tolerated foreigners and inferior

aides, but they emigrated thither (or remained where they were exiled)

where their profession was still understood and appreciated: in blood

feudal Central Arabia. |

| Footnotes | |

| For lack of time, we can't offer still the English version of Footnotes; please be patient. Note that the original English text has a slightly different counting of Footnotes; here we stuck to the German version. | |

| 1)

The

expositions given here in section I are a summary of the main results of

my monographs Über den Ur-Qur`an (Erlangen, 1974) and Die

Wiederentdeckung des Propheten Muhammad (Erlangen, 1981). In this section,

therefore, notes are given only concerning problems discussed subsequent

to these works. Main

Text 2) s. dazu Albert Schweitzer, Das Messianitäts- und Leidensgeheimnis. Eine Skizze des Lebens Jesu, 3.Aufl. Tübingen 1956 (1.Aufl. 1901). Main Tex 2A) "Haram and Hawtah, the Sacred Enclave in Arabia," in A. Badawi (ed.), Mélanges Taha Husain (Cairo, 1962); see also Gerd R. Puin, "The Yemeni Hijrah Concept of Tribal Protection," in Land Tenure and Social Transformation in the Middle East, ed. T. Khalidi (Beirut 1984) Main Text 3) T. Kronholm, Dependence and Prophetic Originality in the Koran, Orientalia Sueccana 31/32 (1982/83), 64. Sehr ähnlich E. B. Serjeant, a.a.O., 57. Main Text 4) s. C. H. Becker, Christliche Polemik und islamische Dogmenbildung, in: Islamstudien, 1.Bd., Leipzig 1924, 433, 435, 442-445. Main Text 5) s. die etymologischen Ausführungen von W. F. Albright, The High Place.... a.a.O., 247-253; dazu G. Lüling, Archaische Wörter und Sachen im Wallfahrtswesen am Zionsberg, Dielheimer Blätter z. AT (DBAT) 20 (1984), 52-59.Main Text 6) Otto Eissfeldt, Der Gott des Tabor und seine Verbreitung, ARW 31 (1934), 40f. Main Text 7) G. Lüling, Archaische Wörter und Sachen... a.a.O.(hier A.5), 52ff mit A. 5. Main Text 8) G. Lüling, Das Passahlamm und die Altarabische Mutter der Blutrache, die Hyäne, ZRGG 34 (1982), 130-147. Main Text 9) G. Lüling, Archaische Metallgewinnung und die Idee der Wiedergeburt, ZRGG 37 (1985) 22-37. Main Text 10) Eine der jüngsten Stellungnahmen zu diesem Thema: Ralph Stehly, David dans la Tradition Islamique à la lumière des Manuscrits de Qumran, R.H.P.R. 1979, 357-367 Main Text 11) s. dazu R.W. Hynek, Golgotha im Zeugnis des Turiner Grabtuchs, 2.Aufl. Karlsruhe 1950, 44ff; Zur jüdischen Tradition eines lahmen Jesus-Bileam s. R.T. Herford, Christianity in Talmud and Midrash, Neudruck New Jersey 1966, 64-78 Main Text 12) Wichtig wäre auch das Argument der höhenkultisch-totemistischen Symbolik der jüdischen Tradition; s. dazu z.B. Joseph Gutmann, Leviathan, Behemoth and Ziz: Jewish Messianic Symbols in Art, HUGA 39 (1968), 219-230. Main Text 13 G. Lüling, Archaische Wörter und Sachen... a.a.o. (hier A.5), 94-98. Main Text 14 Walter Beimpell, Der Ursprung der Lade Jahwes, OLZ 19 (1916), 326-331; W. B. Kristensen, De Ark van Jahve, Amsterdam 1933 (Meded. d. Kgl. Akad. v.W., Afd. Letterk., Deel 76 Ser. V, Nr.5, 136-171; G. Lüling, Archaische Wörter und Sachen... a.a.O (hier A.5), 51ff. Main Text 15 G. Lüling, a.a.O., 82ff Text 16 al-Kulini, Al-Usul min al-Kgfi, 3 Teheran 1388, Teil 1, 238 Main Text 17 Claude Lévi-Strauss, Das Wilde Denken, Frankfurt a.M. 1968, 27 Main Text 18 Urban-Bücher Nr. 90, Stuttgart-Berlin-Köln-Mainz 1966. Main Text 19 Arnold Gehlen, Urmensch und Spätkultur, Bonn 1956, 262; auch die Altorientalistin Margarete Riemschneider, Fragen zur vorgeschichtlichen Religion, 1. Augengott und Heilige Hochzeit, Leipzig 1953, verwendet sinnvollerweise diesen Begriff. Main Text 20 Arnold Gehlen, Urmensch und Spätkultur, 273f; s. auch Adolf Ellegard Jensen, Mythos und Kult bei Naturvölkern, Wiesbaden 1951, 249-323: Über die Magie. Main Text 21 Arnold Gehlen, Urmensch und Spätkultur, 278 Main Text 22 J. Wellhausen, a.a.O., 1 u. 6. Main Text 23 s. z.B. seine Fehlurteile bezüglich der im Urislam als Götzendienst verurteilten christlichen Bilderverehrung in Mekka; vgl. G. Lüling, Die Wiederentdeckung des Propheten Muhammad, über Namensindex: Wellhausen. Zurück Main Text 24 Hugo Greßmann, Der Messias, Göttingen 1929, 231, 276, 336. Zurück Main Text 25 Heike Friis, Ein neues Paradigma für die Erforschung der Vorgeschichte Israels? (aus dem Dänischen übersetzt von B.J. Diebner), Dielheimer Blätter z. AT 19 (1984), 11; s. auch Heike Friis, Das Exil und die Geschichte, DBAT 18 (1984). Zurück zum Text 26 Moshe Weinfeld, Getting at the Roots of Wellhausen's Understanding of the Law of Israel, On the 100th Anniversary of the Prolegomena, Institute for Advanced Studies, The Hebrew University Jerusalem, Report No. 14, 1979 Zurück zum Text 27 J. W. Hirschberg, Jüdische und Christliche Lehren im vor- und frühislamischen Arabien, Krakow 1939, 38 spricht von "der längst widerlegten Theorie Dozy's" ohne Hinweis auf irgendeinen Widerleger. Die sehr umfangreiche "Widerlegung" von K. H. Graf in ZDMG 19 (1865), 330-351 wirkt hilflos, ist insbesondere heute unhaltbar wegen seiner unkritischen Anerkennung des Pentateuch als historische Quelle. Das gleiche gilt von Th. Nöldekes Abhandlung "Die Amaleqiter" (Orient und Occident 2/1864, 614-655), der alle arabischen Nachrichten als aus AT-Texten herausgesponnen betrachtet (heute aufgrund der keilschriftlichen Forschungsergebnisse nicht mehr haltbar). Nöldeke nennt Name und These Dozys nicht, nimmt aber detailliert zu allen in Dozys These angesprochenen Themen Stellung, so daß sich der Verdacht aufdrängt, daß Nöldeke die Thesen Dozys bereits kennen gelernt hatte (vor Veröffentlichung als Manuskript oder aus der niederländischen Fassung) und ohne Nennung Dozys zu seinen Thesen Stellung genommen hat. Zurück zum Text 28 R. Dozy, a.a.O., 70ff Zurück zum Text 29 R. Dozy, a.a.O., 40ff Zurück zum Text 30 R. Dozy, a.a.O., 58ff Zurück zum Text 31 s. dazu Bernd Jörg Diebner, Erwägungen zum Thema Exodus, in: Festschrift Wolfgang Helck, Hamburg 1984 (= Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur Bd. 11), 597f (III. u. IV); B. J. Diebner und Hermann Schult, Thesen zu nachexilischen Entwürfen der frühen Geschichte Israels, DBAT 10 (1975), 41 ff; B.J. Diebner und H. Schult, Argumente ex silentio. Das Grosse Schweigen als Folge der Frühdatierung der 'alten Pentateuchquellen', DBAT 11, SEFER Rendtorff, Dielheim 1975, 24-35. Zurück zum Text 32 R. Dozy, a.a.O., 180ff Zurück zum Text 33 R. Dozy, a.a.O., 58-65. Zurück zum Text 34 s. dazu Hugo Winckler, Alttestamentliche Untersuchungen, Leipzig l892, 120ff. 146-156, 168ff; Hugo Winckler, Musri, Melukhkha, Ma'in. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des ältesten Arabien und zur Bibelkritik, (Mitteilungen der Vorderasiatischen Gesellschaft 1) Berlin 1898, 32-37; Hugo Winckler, Altorientalische Forschungen I, Leipzig 1893, 24-41: Das nordarabische Land Musri in den Inschriften und der Bibel; Fritz Hommel, Vier neue arabische Landschaftsnamen im Alten Testament, München 1901. Wincklers und Hommels Arbeiten rechnen mit einer falschen, die Minäerherrschaft zu früh ansetzenden Chronologie. Ihre Ausführungen zum AT sind aber unter Ansetzung des heute allgemein anerkannten Spätansatzes des Minäertums noch bedeutsamer. Zurück zum Text 35 Hugo Winckler, Geschichte Israels in Einzeldarstellungen, Leipzig 1895, 55-59 Zurück zum Text 36 s. dazu die hier A.31 angegebene Literatur. Zurück zum Text 37 Trude Weiß-Rosmarin, Aribi und Arabien in den babylonisch-assyrischen Quellen, Journal of the Society of Oriental Research 16 (1932), 3 Zurück zum Text 38 R. Dozy, a.a.O., 134 ff, 186ff Zurück zum Text 39 Manfred Kropp, Die Geschichte der 'reinen Araber' vom Stamme Qahtan, Dias, Heidelberg 1975, Bd. 1, 76a sieht in der Einteilung "l. und 2. Gurhum" einen "Kunstgriff der Genealogen", die "die alten Völker einfach verdoppeln". So leicht sind die Probleme nicht zu lösen! Zurück zum Text 40 R. Dozy, a.a.O., 154. Zurück zum Text 41 R. Dozy, a.a.O., 94ff, 139ff Zurück zum Text 42 T. Fahd, Gerrhéens et Gurhumites, Festschrift Berthold Spuler, Leiden 1981, 67-78, spez. 71 A. 20 Zurück zum Text 43 T. Fahd, a.a.O., 74. Nach Fertigstellung dieser Abhandlung sehe ich, daß T. Fahd das Buch und also auch die These Dozy "Die Israeliten in Mekka seit der Zeit Davids" vor Abfassung seines hier zitierten Aufsatzes bereits kannte (siehe sein "Le Panthéon de l'Arabie Centrale à la Veille de l'Hégire", Paris 1968, 264). Wie ist sein Schweigen zu Dozy zu erklären (siehe hier A. 27)? Zurück zum Text 44 Zur religiös-rituellen Sicherstellung von Vermögenswerten in den minäischen Levitentexten siehe H. Grimme, Der südarabische Levitismus, Le Muséen 37, 172 f, 178 f, 182, 186, 189 f, 193 f; ferner Martin Hartmann, Die Arabische Frage, Leipzig 1909, 35 ff; Alois Sprenger, Die Alte Geographie Arabiens, Bern 1875, 224 f; D. S. Margoliouth, The Relations between Arabs and israelites prior to the Rise of Islam, London 1924, 62; de Lacy O'Leary, Arabia before Muhammad, London 1927, 182; Adolf Grohmann, Arabien, München 1963, 136-138 Zurück zum Text 45 s. dazu A.H.J. Gunneweg, Leviten und Priester, Göttingen 1965, 38-44 Zurück zum Text 46 s. dazu Otto Bächli, Amphiktyonie im AT, Basel 1977 und Herbert Donner, Geschichte des Volkes Israel und seiner Nachbarn in Grundzügen, Göttingen 1984, 72ff u. 146ff. Zurück zum Text 47 Zur These einer ursprünglichen Herkunft der Hebräer ('lbri = Wüstendurchquerer von Südarabien nach Midian und Mesopotamien) aus dem Weihrauchfernhandel des 3. und 2. Jahrtausends v.Chr. können wir hier nicht Stellung nehmen. Doch ist dieses Urteil von Carl Rathiens, Kulturelle Einflüsse in Südwestarabien von den ältesten Zeiten bis zum Islam, Jahrbuch f. Kleinasiatische Forschung 1 (1950), 13 sehr bedenkenswert. Zurück zum Text 48 s. dazu Roland de Vaux, a.a.O., 272 mit A 37 Zurück zum Text 49 zitiert nach R. T. Herford, a.a.o. (hier A.11), 378 Zurück zum Text 50 ich nenne hier nur R. T. Herford, Bernhard Kellermann, A. Buchler (Festschrift Hermann Coben, Berlin 1912) und meinen hochverehrten Lehrer Hans-Joachim Schoeps. Zurück zum Text 51 s. Z.B. Karl Georg Kuhn, Giljonim und Sifre Minim, Festschrift Joachim Jeremias, Beihefte zur ZNW, 26 (1960), 36ff, 55ff Zurück zum Text 52 R.T. Herford, a.a.O. (hier A.11), 29ff, 297ff Zurück zum Text 53 Zur Entstehungszeit des Monotheismus s. Othmar Reel (Hg.), Monotheismus im alten Israel und seiner Umwelt, (= Biblische Beiträge 14), Freiburg (CH) 1980 und Bernhard Lang (Hg.), Der Einzige Gott. Die Geburt des biblischen Monotheismus, München 1981 Zurück zum Text 54 R.T. Herford, a.a.O., 293ff Zurück zum Text 55 P.T. Herford, a.a.O., 177ff Zurück zum Text 56 R.T. Herford, a.a.O., 181 u. 331 Zurück zum Text 57 Hubert Grimme, Muhammad, München 1904, 11; ausführlicher Fritz Hommel, Grundriß der Geographie und Geschichte des Alten Orients, München 1904, 566ff Zurück zum Text 58 s. dazu de Lacy 0'Leary, Arabia before Muhammad, London 1927, 57. Zurück zum Text 59 Diese Verschmelzung der Simeoniten mit den 1. Gurhum drückt sich auch in der starken arabischen Tradition aus, daß Ismael, der Sohn der Hagar, sich mit einer Gurhumitin verheiratete. Im übrigen liegt in dieser Verschmelzung der Ismaeliten mit diesen 1. (hauptsächlich levitischen) Gurhum allen Umständen nach auch der Grund dafür, daß in Gen. 49,5-7 (im sogenannten "Jakobssegen", der höchstwahrscheinlich erst in nachexilischer Zeit verfasst wurde) die Stämme Simsen und Levi zu zurücksichtslos-gewalttätigen Komplizen erklärt und verflucht werden. Zurück zum Text 60 Fritz Rommel, Nachträgliches zum Reich von Ma'in, Aufsätze und Abhandlungen arabistisch-semitologischen Inhalts, Erste Hälfte, München 1892, 128: "daß ich jetzt zu der Überzeugung; gelangt bin, daß Minaioi und Ma'in von Haus aus verschiedene Namen sind"; ähnlich auch schon Alois Sprenger, Die Alte Geographie, 231. Zurück zum Text 61 Zu dieser Tendenz s. Carl Rathjens, a.a.0. (hier A.47), 22f und de Lacy O'Leary, a.a.0. (hier A.58), 106. Zurück zum Text 62 Die verwandtschaftlichen Beziehungen zwischen den (gurhumitischen) Minäern in Dedan und Ma'in dürfen wir auch zwischen diesen Minäern und den autochthonen Gurhum in Gerrha voraussetzen (zumindest durch Heiratspolitik geknüpfte Verwandtschaftsbeziehungen). Zurück zum Text 63 Freya Stark, The Southern Gates of Arabia, London 1946 , 266 Zurück zum Text 64 R.B. Serjeant, a.a.0. , 55' t 52 f. Zurück zum Text 65 s. dazu A. Grohmann, Arabien, München 1963, 124f , 130, 273f (Stellungnahme zu A. van Branden). Grohmann zeigt 127 seine grundsätzliche Fehleinschätzung der südarabischen "Verfassungssituation", indem er sie als einen "ungeheuren Fortschritt" (!! ??) gegenüber dem Absolutismus in Ägypten und Babylon darstellt. Die Ratsversammlung unter dem Kabir heißt maswad, ein hebräisches Wort! Die Hebraismen der minäischen Kultur bilden ein eigenes umfangreiches Kapitel. Zurück zum Text 66 R.B. Serjeant, a.a.O., 53 f und W.H. Ingrams, Hadhramaut, Geographical Journal 88 (1936), das Foto gegenüber S. 542: "The Mansab of Meshed" mit seinem "Leviten', 1). Zurück zum Text 67 A. H. J. Gunneweg, a.a.o. (hier A.45), 58 schreibt noch: "Ein ganzer Stamm oder gar ein ganzer Volksstamm von lauter Priestern ist - auch noch als Fiktion -, zumal in der für das ältere (G.L. : Stämme-)System von Eponymen vorauszusetzenden, früheren Zeit, schlechterdings" undenkbar. Zurück zum Text 68 "Sarazenen" finden sich etwas später als die Hagarener zum ersten Male bei Dioskuridee. Diese Datum des ersten Erscheinens in der Literatur kann natürlich nicht als das Datum des ersten Gebrauchs dieser Bezeichnung gelten. Zurück zum Text 69 Hieronymus in seinem Kommentar zu Ezechiel, zitiert nach EI (deutsche Ed.) s.v. "Sarazenen"; a. auch M.F. Nau, Un Colloque du Patriarche Jean avec l'Emir des Agaréens, Journal Asiatique, 11. Serie, Tome V, 238 note 3 Zurück zum Text 70 s. dazu G. Lüling, a.a.0. (hier A-5), S. 91 mit A. 94 : kn ist etymologisch-semasiologisch die "Maskierung, Kriegsbemalung": lat. conari, griech. konein, kindyneuein, kinesis (in seiner archaischen Grundbedeutung: "Krieg beginnen"). Zurück zum Text |

|

|

|

||